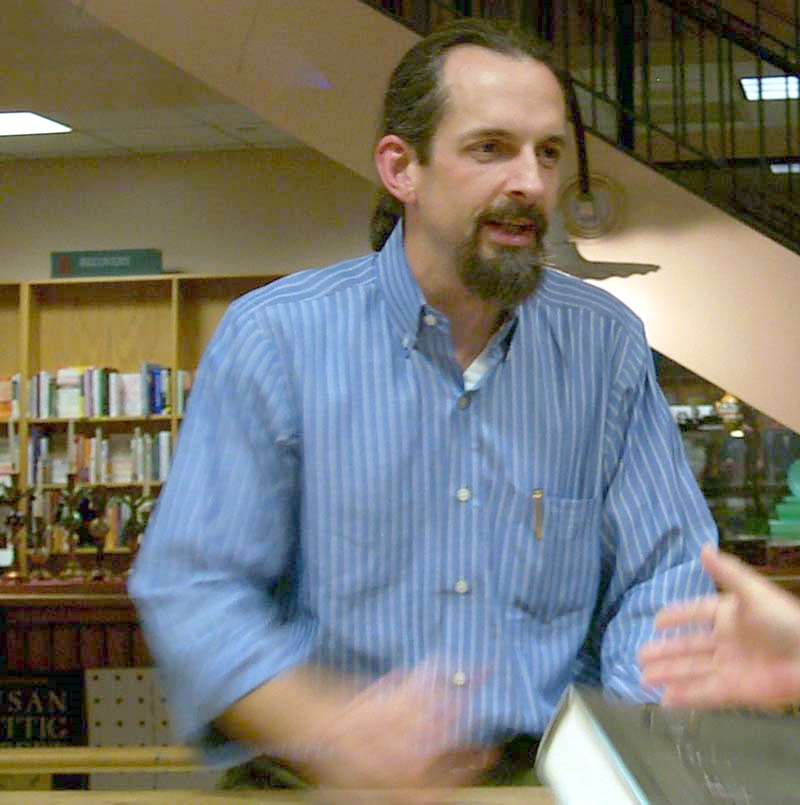

Neal Stephenson in Austin, October 4, 2004

On October 4, 2004 Neal Stephenson was at Book People in Austin, TX, where he read an excerpt from his then-latest book, “The System of the World” (the third and the last novel in The Baroque Cycle), gave a talk and signed books. Here are the questions the audience asked him, and his answers. (The places I couldn’t hear very well I paraphrased the best I could; they are in angle brackets.)

Q1. How do you your historical research?

Q3. Do you have any plans to write more nonfiction?

Question 8. When you were here last October, you talked about how you explored history for Cryptonomicon, and the Baroque Cycle. Do you think you reached the end of that?

Q9. Some people are dissatisfied with endings of Neal Stephenson’s books…

Q13. What are your favorite books of all time?

Q14. Are you still a speed metal fan?

Question 1. How do you your historical research?

NS. Research is a pretty fine word for it. Compared to what historians do, I’m pretty lightweight. I find books in languages that I know, meaning English, and I read them. I take notes as I go in no particular order. I have a stack of notebooks, and because they are completely unindexed, every time I want to find something in a notebook, I have to search through all of them. Which is actually a useful thing because it increases serendipity. Reminds me of something I had forgotten about, something that ties in an unexpected way. I acquired a fair number of books for this, got a copy of Winston Churchill’s [book_title], got some maps of London, miscellaneous reference volumes, things I copied off of microfilms. By the time I got to the end of the… or even halfway through the project, in my little cockpit where I work I was completely surrounded by all this stuff, so that if I needed to look something up, I could usually pick it up within arm’s reach. So for the last couple of years the only… I didn’t really have to… I would have to go out and do surgical strikes on the library to pick up the one very specific piece of information. [I now own more than enough books for general research.]

Question 2. Can you comment briefly on your perception of status of science and philosophy in the current education system?

NS. My thoughts on the status of science and philosophy in the current education system? That’s a mighty tempting opportunity to clamber up a soapbox, which I thank you for [Audience laughs].

I’m gonna be a little moderate, I don’t want to get all soapboxy. There’s this kind of a paradox right now: we’re a really high-tech country that’s completely dependent on science. We are turning out some really idiosyncratic bright science people, but we’re not that good at generating a large middle class of engineers and scientists. We got a few really bright people and it turns out that a lot of those people didn’t get a whole lot of help from their schools. I commonly hear stories of people like this, who just had to do it themselves. They just had to be complete autodidacts to learn what they know. But that’s not to say that it couldn’t be better. It’s pretty dismal.

From what I’ve seen in elementary school, you don’t see a lot of teachers who have a lot of science under their belts. So they’re kind of reading from books, they’re doing their best. But by the time the kids have gotten to 5th or 6th grade they really need specialized science teachers and math teachers, because they are ready to handle material that a lot of their teachers don’t know. It’s really hard to get people who are good at science and math to go into that profession, because it’s just brutal.

And philosophy — I don’t think it’s taught at all, as far as I know, unless you make it all the way to college and go seek out a course in that topic.

I don’t know what to do about it, but that’s my incredibly dismal and depressing worldview.

Any other questions? Now the room is afraid. [Audience laughs]

Question 3. Do you have any plans to write more nonfiction?

NS. I don’t have any plans one way or the other right now.

Another voice from the audience: Tired?

NS. I’m not that tired, but the way it works is that when you finish a book, then it’s kind of in the pipeline for the bigger part of a year. While it’s in the pipeline, it’s very hard to get going another project, because you may have two or three weeks quiet, but then suddenly you’ve got to read the page proof, you’ve got to work on something — you’ve got to be an author, not just a writer. So I haven’t even tried to get going on anything, cause usually when I’m going on something I’m very excited about it, I’m pretty obsessively focused on it, and to be interrupted all the time is just hell. It makes me a very unpleasant person to be around. So I’ve avoided it, and I’m still avoiding it, cause I still got a few weeks of […] And then, you know, it’s all on the table, there is no next project queued up and ready to go. It might be nonfiction, writing about science and technology issues, there aren’t too many people doing that. But if I go out and do it just to be altruistic, it’s gonna suck.

Question 4. What are you reading now?

NS. On the plane today, dodging volcanic eruptions and lightning bolts (he refers to St. Helen’s eruption he got to see soon after taking off from Seattle that morning), I’ve been reading “Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norell”, or maybe it’s the other way around. That’s the new book by Susanna Clarke. I read China Mieville’s “Iron Council” over the summer I’m always reading some kind of history book. I read Lincoln-Douglas Debates over the summer, I read some Texas history.

Question 5. I’m wondering if you have any additional thoughts on what to do with metaweb? Do you think it’s a good forum to explore how can we maybe get Enlightenment to start again? [Audience chuckles]

NS. I’m not sure if we want to start it again, but I know what you mean. [Explains to the audience:] He’s asking about metaweb; currently it’s a website that doesn’t have a heck of a lot on it, other than some annotations of this series of books.

Yeah, I mean, it’s part of a larger, mostly submerged project to work on making the Internet a better tool for explaining things, which it is not very good at now. It’s not yet developed enough to serve that purpose. I hope it will, but it’s almost entirely out of my hands. All I can do is attack it at a very nitty-gritty level, logging on from time to time and putting up some annotations of my books.

I also put up a couple of annotations of Heinlein’s book called “Have Spacesuit, Will Travel”, just in hopes of getting people into spirit, but it’s not grown a heck of a lot. So, stay tuned, but […]

Question 6. Now that you’ve been through this process, do you see yourself engaging in the long, long form again?

NS. Compared to what?

[Inaudible answer]

NS.You mean, writing another thing like this?

The author of the question. Well, no, yeah, something huge… long form…

NS. Oh yeah, I mean, yeah, that’s where it is. My basic opinion is that if this society wants to support me while I work for something for seven years, then I shouldn’t turn up my nose at an opportunity like that. If I can keep stringing together those kinds of jobs, then that’s probably the kind of highest and best way to spend my time. I think it would be sinful not to take advantage I’ve been given, if a lot of people read it. Not that a lot of people read it, but they seem to be buying it. [Audience laughs.]

Question 7. You spend that much time just setting the stage for the final conflict. Your prose, your writing style alone is what keeps people coming back. Is that daunting to your publisher?

NS. Well, the observation that I’ve made is that people, certainly the ones who are into SF and fantasy, also other… historical novels, people aren’t the least bit bothered by the length, as long as they are enjoying themselves. So you can throw, and other writers have thrown, amazingly long series, amazingly long books out in public, and if you’re not enjoying yourself, if you’re not enjoying the writer, you simply aren’t gonna read those books, period. If you are enjoying it, then there’s more to enjoy, and people aren’t bothered by the length. They even write you wounded letters to you afterwards: “Why didn’t you say more about this? Why did you go over that part so quickly?”

So I guess I wasn’t very daunted cause I knew there was already some kind of self-selection going on. By the time you get 3 or 4 inches into this series, everyone who’s not having a good time would quit. And then, of course, the other thing that’s obviously doing this, throwing in sword fights and pirate attacks — I mean, we’ve got Leibniz here philosophizing about smoke rings (refers to the passage from “System of the World” he read at the beginning of the talk, Leibniz’s letter to Daniel Waterhouse), but that’s… I kind of tried to sprinkle that material through including lots of sex and violence, to keep things moving.

So I guess I didn’t feel that daunted, and the publisher… you know, I collaborated with the publisher in a pretty reasonable way, so they knew what I was doing. If they were daunted, they showed admirable reserve.

Question 8. When you were here last October, you talked about how you explored history for Cryptonomicon, and the Baroque Cycle. Do you think you reached the end of that?

NS. I’ve temporarily had it with this subject, having been working on it basically for ten years, which is when I started writing “Cryptonomicon”. So I feel that to now sit down and dive into a novel about Waterhouses and Shaftoes and computer engineers in 19th century or whenever, would be a mistake. But also to rule it out, to say that I’ll never do it, would be a different kind of mistake. So I’m pretty sure it’s not what I’m gonna do next. I may never do it. But I’m not ruling it out.

Question 9. <Says that some people are dissatisfied with endings of Neal Stephenson’s books, or that they say he can’t write good endings.>

NS. Well…

The person who asked the question. I’m not one of them. [Audience laughs]

NS. I know they’re out there.

It depends on the book. It’s certainly not the case that I’ve got one Procrustian rule of what an ending is supposed to do and I try to do that for every book. [Readers’ dissatisfaction with endings of Stephenson’s books] started with “The Diamond Age”, which does have a very controversial ending. Before that, no one ever griped about the ending of “Snow Crash”. The “Snow Crash” has a pretty thorough ending, where bad guys and good guys fight, things blow up, some people die, some people live happily ever after, and it’s all pretty wrapped up, so nobody complained about it. And then I started to see after “The Diamond Age” came out: “Oh yeah, Stephenson can’t write endings”. I say, look at the ending of “Snow Crash”. What more do you want?

And so at the ending of this (Baroque Cycle), I really did go out of my way, not just cause people griped about it, but for other reasons too. To really wind it up. So this ending was plotted out to the nth degree, and everything gets settled, and there should be no doubt in anyone’s mind they’ve just read a real ending. [Audience laughs]

Question 10. Can you talk about Waterhouse and Shaftoe characters, why they appeal to you and why they showed up in the last 4 books?

NS. To really do that would require me to engage in a lot more of self-analysis. I’m not just trying to be coy. I really… I think a lot of people look at something like this and think I’ve got a superego that was kind of planning the whole thing and deciding what to do. It wasn’t like that. Waterhouse and Shaftoe characters came from wherever characters come from, and I had a good time with them, and decided to follow a similar pattern in the Baroque Cycle. When I started the Baroque Cycle, I didn’t really have a sure idea how big it might be, so starting from that, their family trees developed, their stories developed, and they became these big, complicated characters, but it was never out of some kind of plan or scheme.

I don’t know why like them. It’s like asking why I like a friend of mine. I can stand here and come up with some kind of pokey reasons, but that would just be… that’s just me trying to answer the question. [It won’t be a true answer.]

Question 11. I was just wondering if [some author of historical fiction and/or his book] caught your eye while you were writing this.

NS. Some books like that caught my eye when I was writing this. I did everything I could not to read them, because I didn’t wanna get influenced by what other people did. (Refers to the book the author of the question asked him about): I got it sitting there pristine on my shelf. I bought the hardcover, put it on the shelf and haven’t read it yet. I’d like to read it. But I’ve read a lot of non-fiction that comes of this era, like a book about thieves (?) and quite a few other, but not the fiction.

Question 12. Did you develop a lot of material for “Cryptonomicon” and the Baroque Cycle that’s not included in the final versions?

NS. The original grand plan, the kind of grand plan that fills the dustbins of history, was that there was going to be a [future story that takes place after the events described in “Cryptonomicon”]. I was working on a chunk of it [that was set in the future]. It was a lot slower to develop. It wasn’t hitting right. When I really sat down and tried to make some headway on that, I finally figured out what the problem was. I could tell there was a problem. I realized that in order to solve the problem I had to go back and write this (points to a copy of “System of the World”). So I did that. So the logical thing then would be, OK, I got that squared away, now I can go back to work on the future. Part of the thing is, I may do that, but it’s not what I’m going to do next. I need a break from these people. And I suspect that everything I wrote seven or eight years ago on the future part of it will have to be scrapped, because that’s a hell of a lot time in the career of a writer.

Question 13. What are your favorite books of all time?

NS. Favorite books of all time? “Moby Dick”… I’m really not good at these questions. As soon as I walk out, I’ll have 20. But when I stand in front of a room of people, trying to remember my favorite books, I draw a complete blank. I liked “Gravity’s Rainbow”, “Infinite Jest”. I like history books. But I don’t have any… I don’t feel I can answer these questions very well. It’s not like there were one or two books that changed my life.

Question 14. Are you still a speed metal fan?

NS. No, I’m not. I realize this, cause [everything I have is in the iPod, and I usually play it in the shuffle mode], and there’s a button you can hit to jump to the next song. And I’m finding that every time one of my old sludgy Seattle speed metal bands comes on, I reach for that button. I’m not proud of it, you know. I wanna be the kind of guy who listens to that, but I’m not anymore.

Q. I was going to ask a question about time. It’s kind of fascinating to me that your earlier books had focused on future, and later books focus on past. We live in this time when everybody has a great anxiety about what’s going on in the world, and I guess one of the things that was most interesting to me about “Cryptonomicon” was the way you tackled the contemporary stuff like critique of American politics. There’s so much going on in the world now. I’m just saying that… boy, seems like there’s a lot of really neat material out there for you to work with, in terms of what’s going on in the world…

NS. Well, there is a lot of material. To go out and just directly address current events and try to say something is usually a mistake. It tends to lead to soapboxy writing. People distinctively distrust that. They feel like the author is trying to sell them on an idea.

When 9/11 happened, I took off my futurist hat and heaved it into the dumpster. I didn’t have a clue. I used to hang out with futurists, I got paid to go act as a… you know, to go predict the future. We predicted all kinds of stuff, but never even came close to… If we talked about terrorist attacks, I certainly could not predict that they’ll be carried out with box cutters. So that serves as a caution to any writer who gets too big a head about being able to talk about what’s gonna happen in the future.

And finally what I will say about that, is that the more I look into history, the more I see precedents, obvious precedents for what is going on now. It’s almost more effective to go back in time and write about the precedents, than it is to… It’s kind of like… it’s a bizarre analogy, but experienced programmers always try to avoid rewriting the code. They don’t sit down and reinvent a sorting algorithm, they pick one of the hundred different sorting algorithms that had been studied, debugged and refined, and they just copy it. Because it’s a waste of time to reinvent the wheel.

The more I… I’m tempted just to say, “the older I get”. The older I get, the more history I read, the more I see that we are doing a whole lot of reinventing the wheel and reiterating conflicts that took place hundreds or even thousands years ago. And it’s just strikes me as a big fat waste of time, and it’s almost more efficient to go back and figure out the history. […]