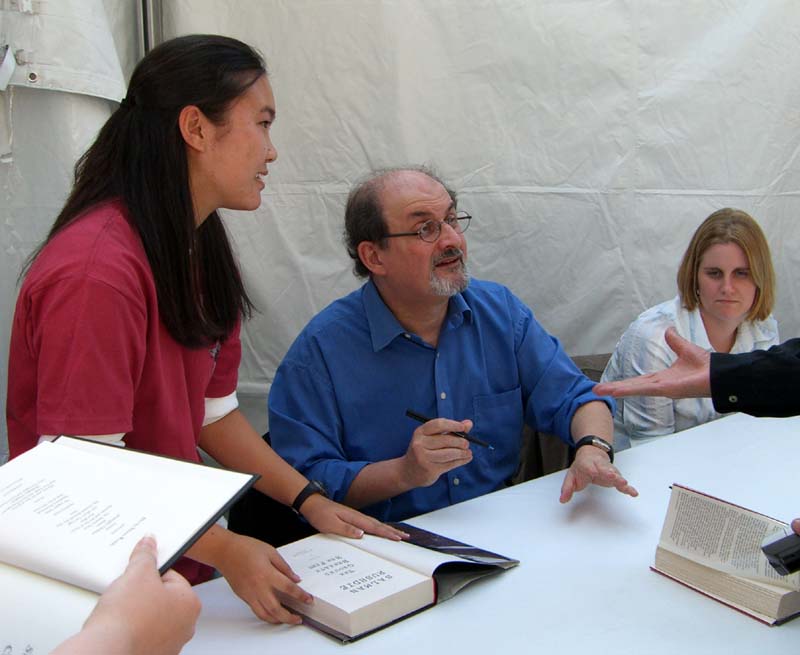

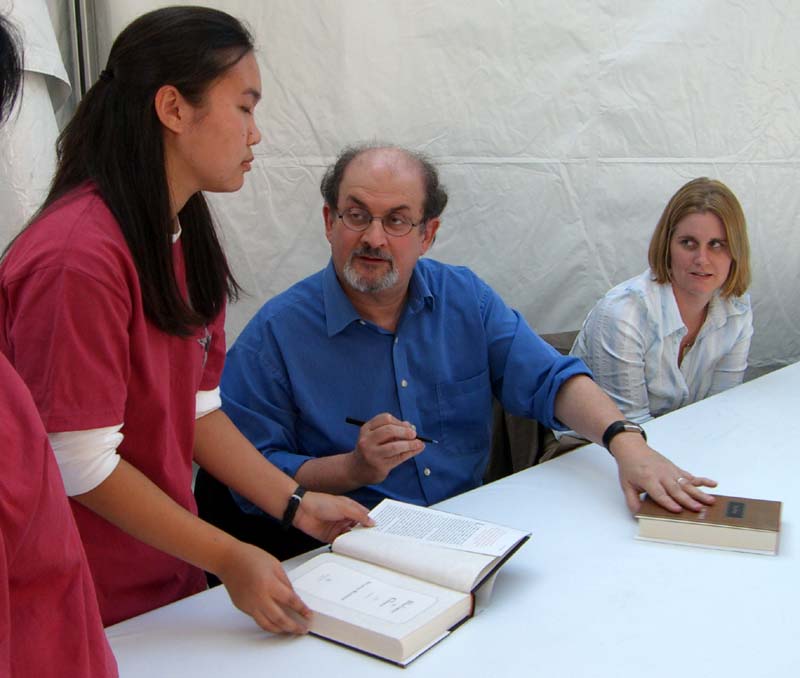

Salman Rushdie at the Texas Book Festival in 2005

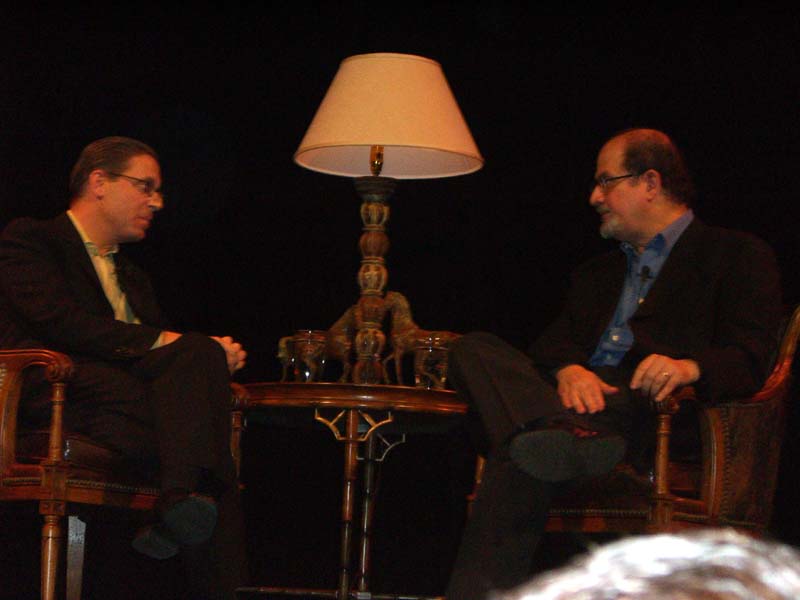

Texas Book Festival took place October 29 – 30, 2005 in Austin, TX, and featured some well known authors like Lemony Snicket and Salman Rushdie. I went to see Salman Rushdie being interviewed by Evan Smith.

Among the topics touched upon at the interview there was the inevitable topic of what Rushdie euphemistically referred to as the publicity agency from Tehran”, writerly quirks (where do characters’ names come from?), which parts of his books are autobiographical; in the Q&A session he gave an advice to an ex-Muslim woman who said her life would be in danger if she publishes a book on Al Qaeda she has written; what could be done to help Americans understand Muslim world, and vice versa; literary criticism summed up in a word “jump”, and other things.

The publicity agency from Tehran

A conversation with Salman Rushdie had to be started with — of course! — the topic of the bounty that was placed on his head by the Iranian ayatolla in 1989. Since then, Iranian government revoked the fatwa, but various Islamist groups continued to have Salman Rushdie on their hit list. The latest call for his assassination was as recent as 2003.

But Rushdie isn’t too worried about what he calls “a publicity agency from Tehran”. He downplays the importance of those assassination verdicts. He semi-seriously, semi-jokingly says those groups continue doing it more out of habit than anything else. Their interest in it has more or less petered out long ago. He finds it funny that the original fatwa was issued around Valentines day (of 1989), and since then every year he gets a little “valentine”. (I wasn’t sure I understood what those yearly valentines were — maybe reminders from certain islamist groups that there is still a bounty placed on his head?)

The interviewer, Evan Smith, also mentioned that a year or two ago when Salman Rushdie wanted to fly to Texas (for a reason that escapes me now), his name turned out to be on the no-fly list and he was refused admission to a plane. Then some good-hearted and rich Texan offered him a seat on his private plane. But Salman Rushdie doesn’t make a big deal out of this incident. He thinks the no-fly list is so flawed that all kinds of people accidentally end up on it, so there’s really nothing ominous about it; he said somebody said that if Kennedy was alive today, he would also be on the list.

Everybody has heard so much about “Satanic Verses”, but have they actually read it?

He is kind of disappointed that people fail to see that his writing is funny. One of the things nobody ever noticed about “Satanic Verses” is the humor in it. Every time he speaks in public, somebody comes up to him at the end of the event and says, we never knew you were going to be funny! I find it kind of depressing, Rushdie says with a smile. Wasn’t it obvious from the book?

He sees it a lot: people forming opinions about “Satanic Verses” without reading it. An elderly Muslim in England, when interviewed on television, said he didn’t need to wade in the gutter to know that it contained filth. Good point! says Rushdie. Another of his, to put it mildly, “detractors”, when pressed for the specifics of what he didn’t like in the book, said “I haven’t read it, books are not my thing”. Rushdie says, that explains everything. So these moments can only be described as funny, even though initially they didn’t seem that way to him.

Evan Smith says: “If you can have a sense of humor about “Satanic Verses”, you can have a sense of humor about everything!”

Writerly quirks

The conversation moves onto Salman Rushdie’s new book, “Shalimar the Clown”. They talk not so much about the book in itself, as about various writerly “moments”, the illogical, quirky aspects of writing itself.

Like character names. Many authors have observed that they often don’t have control of the events in the book: the character starts to “dictate” what happens to him or her. But sometimes authors can’t even choose their character names.

The protagonist in “Shalimar the Clown” is named Max Ophuls, and a lot of Rushdie’s readers asked him why he named his character after an actual, historical person (who, as Google told me, was a movie director). The way Rushdie’s character ended up with this name was almost by accident. Initially Rushdie gave this name to his protagonist as a kind of a placeholder, because he had to call him something. Rushdie was planning to change it at the end. But the character didn’t like to be called anything else! And so the name stuck.

This reminds him of an interview with Paul Simon. Asked about genesis of his song “Graceland”, Paul Simon said that sometimes he writes nonsense lyrics that have the right metrical structure to match the melody of a song he is composing. So he wrote a line “we are all going to Graceland”. He thought it was nonsense because the song was supposed to be about South Africa. Plus, Paul Simon has never been to Graceland. But then the lyrics stuck to the song, and eventually Paul Simon had to go to Graceland. So this kind of thing often happens to Rushdie too.

Rushdie notes that the “real” Max Ophuls’ name wasn’t Max Ophuls. So he thought, if Ophuls could filch a name, Rushdie could filch it back. And his book is about characters who don’t like their names. It is a running gag in the book. They prefer to have a nickname or a stage name. Except for Max Ophuls, who is perfectly happy with his name. (Audience laughs.) He forges names for people to change their identities to help them escape Nazis.

The ocean of stories: does it have anything to do with the internet?

Rushdie is fascinated by how the stories of the world are no longer in separate little boxes, but they all smash into one another. The story of New York city also became the story of Arab world. So he thinks of how to tell the story in this interpenetrated world. After the 9/11 he thought it’s even more important now to recognize that the world is now like this.

In his latest book a murder takes place on the street in Los Angeles, and to understand it you have to understand something about reality of Kashmir, half way over the world.

Then later, during question and answer period, a woman in the audience brings this up again, asking what he meant by the “ocean of stories”. Apparently Rushdie has used this metaphor in some of his writing. She asks if by that he meant internet.

Rushdie replies that “Sea of Stories” was written in 1990, and at that time his relationship with the internet was kind of primitive. No, there is an old [piece of Kashmiri folklore] that literally translates as “an ocean of stories”. So Rushdie thought, wouldn’t it be interesting if there actually was a sea of intertwining stories? Then there were bathtime stories he used to tell his son as he wrapped him in a towel. Rushdie noticed a relation here: bath, sea. “You could dip a mug in the bath and catch a story and drink it.”

He is the second writer I heard saying he dreamed of being a writer as a child. The first was Charles Stross.

Salman Rushdie’s parents told him that as a kid he used to say he wanted to be a a writer, not an astronaut or something. As a 10 or 11-year-old you don’t know what being a writer means, but he thinks he may have had this dream because as a kid he really liked to read. He was a bookworm.

Like most authors, he was influenced by many writers, but the strongest influence on him was European post-war literature, e.g. Calvino. There was a point when he was obsessed by it, he vacuumed it up.

Indian writers were strongly influenced by British literature, and Salman Rushdie wanted to avoid that. He wanted to develop a literary voice that “didn’t belong to the English”. Of course, he says, that’s something American literature did from the beginning. For that reason he really loved the American literature, and Irish too. He was trying to find an image that belonged to him, and American literature helped him to understand how to do it.

A long form of prose narrative didn’t exist in the East for a long time. Long narratives were verse narratives. Rushdie’s formation as a writer was very much on the idea that the generations of Indian writers that came before him were too influenced by the English tradition. And English tradition is very cool and controlled. But Indian reality, one thing you can say about it is it’s NOT cool and controlled. It’s very hard, multifarious, vulgar, smutty, loud. You can’t write about it in English tradition. You have to find other tools to write about it.

He is a proponent of the idea that one should write “close to home”. One of his earlier novels, “Midnight’s Children”, used his childhood as a source material, and doing that allowed him to establish his writing “voice”. Since then he learned to write about material that’s very personal to him. But nowadays he thinks he needs to avoid having “me” characters, because his life is so much in public. When Rushdie writes as as first person, people assume that the protagonist is actually him. For example, his novel “Fury” is about someone who was sexually abused as a child and discovers enormous potential for anger in himself. He suspects he may be a serial killer. When the book came out, every journalist asked: Is that an autobiography? (Audience laughs.)

And speaking about close to home… He talked a lot about Kashmir and the tragedy that befell it lately, the earthquake. In Kashmir it’s really catastrophe. The reason for the earthquake is that the Indian continent was a while ago part of the Antarctica, and then it broke off and floated and smashed into the continent. And in geological timeframe that event is still taking place. The Himalayas are getting higher every year, because the landmass is still moving.

Now there are 3 million people homeless, and Kashmiri winters are cold. You can’t survive Himalayan winter in a tent. The authorities think more people will die from the cold, etc., than were killed in the earthquake. Rushdie thinks the world is suffering from compassion fatigue, because they had to deal with the tsunami, and now there’s an earthquake, etc. And the UN thinks if they don’t get more money by next week, people will start dying. If you have some spare change, he says, please consider giving.

An Indian woman in the audience who, like Rushdie, is an ex-Muslim, says she wrote a book “Emails From Al Qaeda”. Her family says if she publishes this book, Al Qaeda will be after her head. She asks if it’s worth to try to publish it? (She also uses a word “Bushlam” in a sentence, but I don’t remember in what context, since the phrase in which she used it was not very memorable.)

Salman Rushdie thinks the decision should be based on whether she thinks the book will be interesting or not. If it is interesting, then by all means, publish it.

The woman adds that she was molested by a mullah, and that was her main source of anger, that caused her to deconvert from Islam. And 70% of her friends were molested too, but they never talked about it, since no one would believe them. Apparently the audience believed her, though, since they gave her a round of applause.

A man in the audience asks if Salman Rushdie has thought what could be done to help Americans could understand Muslim world, and for Islamic world to understand Americans.

Salman Rushdie thinks there’s an awful amount of disinformation on both sides. Serious Muslim newspapers say Jews perpetrated 9/11. That’s a way to create a demon that has no basis in fact. And in the United States there’s a lot of lumping together the Muslim world into a single monolithic mass. So how do you move beyond stereotyping? he asks.

For example, Muslims in Kashmir, portrayed in his new book, were oppressed by the more radical Muslims. The brand of Islam practiced in Kashmir used to be mild, mystic, influenced by Sufi. It was considered by Jihadists by being too mild and they scared kashmiri into practicing much more conservative Islam, e.g. forcing women to wear veils.

The first victims or Islamic fundamentalism are other Muslims. The first victims of Iranian ayatollah were Iranian people. You have to being to see those separations in the Muslim world, he says. There’s a greater battle happening inside the Muslim world than outside.

Rushdie also thinks that the new technology, such as the Internet, will show the Muslim world what life in the West is really like. But the problem is that most of those countries have very dictatorial regimes that control information. And much of the information that’s being spread is really farce. So the problem is, he says, how do you democratize those countries?

“Jump”

One of the best pieces of literary criticism he received was ‘jump’.

A man in the audience apparently has heard (though I haven’t) about a literary concept Rushdie calls “jump”, because he asks: How do you put “jump” in your novels?

Rushdie first explains what he means by “jump”. A long time ago he showed his oldest son the first 3-4 chapters of his novel and asked how did he like it. The son said, I’ll definitely read it, but… some people may be bored. How so? asked Rushdie. The son said, it doesn’t have enough jump. Rushdie concluded that his son meant acceleration. While telling a story to younger readers the speed at which you tell the story is critical. It may be that you need to tell a story to them at a faster pace than to the adult readers. Rushdie thought, there’s something that could be gained from faster telling.

He thought, the fable is a good model of a story that has a proper pace, because the fable as a form always tells the story quite briskly. It has a tone of voice that if he gets it right, adults could enjoy it in one way and children in another.

So, the concept of “jump” made Rushdie think about the tempo of a story, and that was one of the best literary criticism he ever got.

He remembers a short story by a German writer [Heinrich von Kleist?] “Earthquake in Chili”. The story is 5 pages long. The only thing that happen in the story is absolutely horrible. Terrible things happen and then worse things happen. But the story is told at such breakneck pace that it becomes comical. You start to giggle at those atrocities. If you really accelerate a tragedy, it becomes a comedy. The material is tragic, but the manner is comical, and how interesting that is! It’s messing with people’s minds! Rushdie thought, I can do that too!

Does writing a great book feel similar to reading one?

A guy in the audience says he knows the feeling of being in the middle of reading a really great book. Can you describe to me — he asks Rushdie — what is it like when you’re writing a really great book! Are you sitting in the keyboard and can’t get away from it?

Rushdie says:

There are moments when you write and get excited about what’s happening on the page. Unfortunately, they’re are not frequent enough. Most of the time it takes quite a slog. For me, writing is a very long process. Three times it took me 5 years to write a novel. Only in the very last six months of that period (of writing a novel) I really do begin to get excited. When I finish a book — for example, this book — I do feel it was a good book, but then there is a problem: would anybody agree? Which they sometimes don’t. There are moments when you feel excited about what you’re doing, but there are a lot of moments when you’re not.

He continues:

There is a moment in the movie “Shakespeare in Love”, when he’s writing and looks up and says “God, I’m good!” And I hope Shakespeare said that. I can’t imagine how somebody could write works of Shakespeare and not think they’re good.

Finally, an Indian guy in the audience thanks Salman Rushdie for making Indians proud.